What is Therapy and Why It Works?

Understanding Psychotherapy from a Clinical and Integrative Perspective

Therapy, also known as psychotherapy or talk therapy, is a structured process through which individuals work with a trained mental health professional to explore thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. While it has taken many forms throughout history, modern psychotherapy combines scientific methods with human connection to support healing and psychological growth.

In Islamic Psychology, as well as in contemporary clinical practice, therapy is not merely a treatment for mental illness. Rather, it is a space for meaning-making, self-regulation, and transformation. But what exactly makes therapy effective?

What Is Therapy?

Therapy refers to intentional psychological support that helps individuals better understand themselves, manage distress, and improve overall well-being. It typically involves regular sessions with a licensed professional, such as a psychologist, psychotherapist, or counselor.

Why Does Therapy Work?

Therapy works because it creates a safe, structured, and relational space where individuals can explore their experiences without judgment. Multiple factors contribute to its effectiveness:

1. The Therapeutic Relationship

Research consistently shows that the quality of the therapeutic relationship—also called the “therapeutic alliance”—is one of the strongest predictors of success in therapy (Wampold, 2015). This includes empathy, trust, and mutual respect between client and therapist.

2. Self-Awareness and Insight

Through guided reflection, clients gain insight into their thought patterns, emotional reactions, and behaviors. This awareness often leads to new perspectives, healthier decisions, and emotional regulation.

3. Evidence-Based Techniques

Therapists use validated tools and interventions tailored to the client’s needs. For instance, CBT offers structured exercises for managing anxiety or depression, while trauma-focused approaches help process and integrate difficult experiences.

4. Emotional Regulation

Therapy provides techniques that calm the nervous system and enhance resilience. Over time, clients learn to tolerate distress, cope with uncertainty, and respond rather than react.

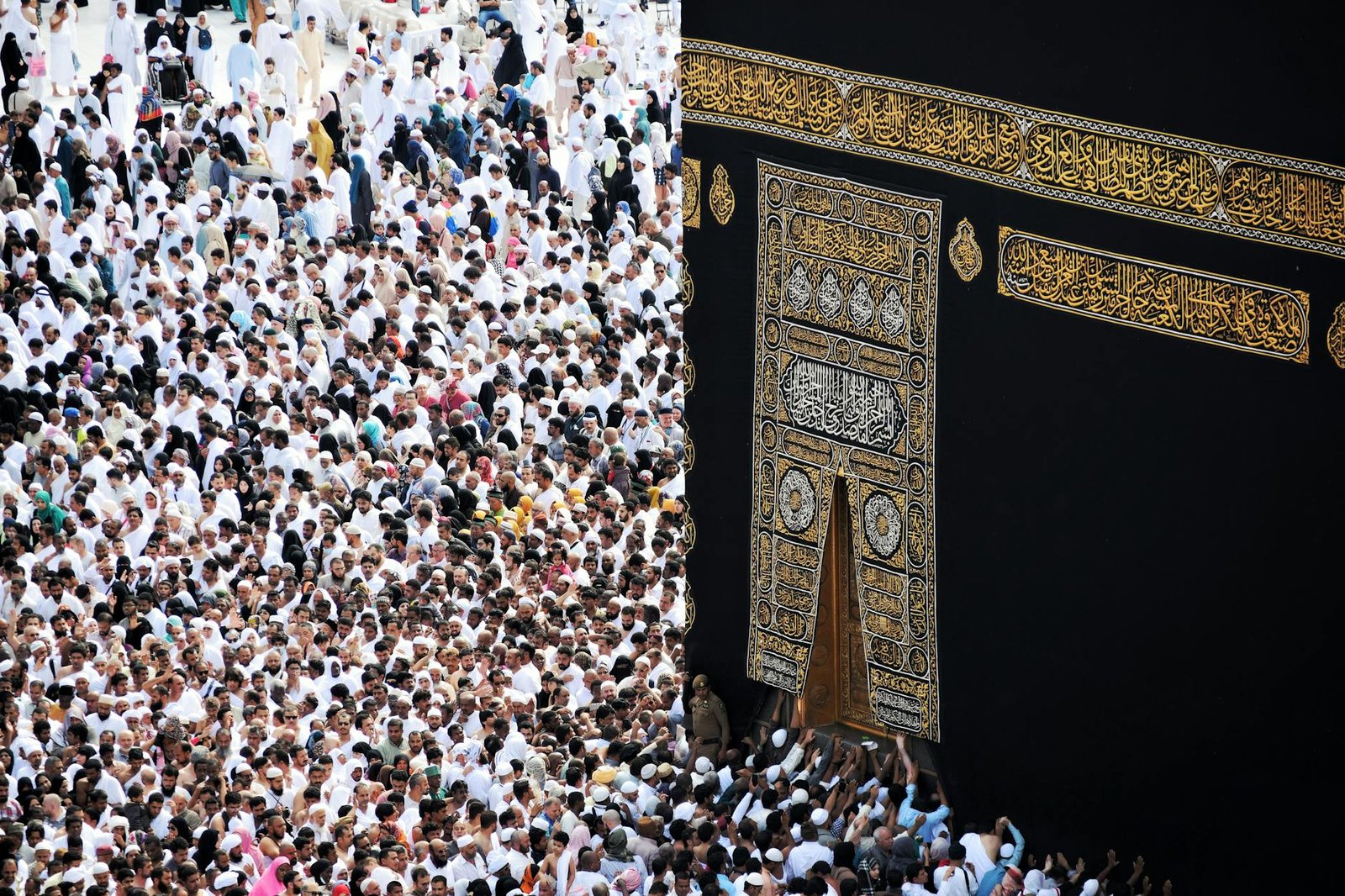

5. Integration of Faith and Meaning

In approaches such as Islamic Psychology, therapy also supports the client in aligning their inner experience with their values and beliefs. This integration adds depth and meaning to the healing process.

Therapy Is Not Just for “Problems”

Although therapy is often sought during periods of crisis, it is equally valuable for:

- Personal development

- Improving relationships

- Clarifying life purpose

- Spiritual reflection

- Preventive mental health care

Therefore, therapy should not be viewed as a last resort. Instead, it can serve as a proactive tool for anyone seeking clarity, growth, or support.

Common Misconceptions About Therapy

“Therapy is only for people with serious mental illness.”

In reality, therapy benefits people with a wide range of concerns—from stress management to identity issues, grief, or decision-making challenges.

“Talking to a friend is the same as therapy.”

While friendships are crucial for emotional support, therapy provides professional training, confidentiality, and intentional frameworks for change.

“Therapy is un-Islamic.”

On the contrary, therapy can align beautifully with Islamic values when guided by principles of compassion (raḥma), introspection (muhāsaba), and healing the nafs. Many Muslim scholars throughout history, including Al-Balkhi and Al-Ghazali, emphasized inner work as part of the spiritual path.

Is Therapy Right for Me?

Therapy is a deeply personal process. Some people see changes after a few sessions, while others may benefit from long-term work. What matters most is showing up, being open, and finding a therapist who feels like a good fit.

Is Therapy the Same as Talking with a Friend?

While talking to a trusted friend can be comforting and helpful, therapy offers something very different.

Here’s how therapy and friendship differ:

| Therapy | Friendship |

|---|---|

| Conducted by a trained professional with years of education and supervised experience | Based on mutual emotional support |

| Confidential and ethically bound to protect your privacy | May involve shared stories and opinions |

| Structured, with clear goals and techniques based on psychological research | Informal, spontaneous conversations |

| Focused entirely on you and your growth | Mutual sharing of emotions and challenges |

| Emotionally safe environment free of judgment, criticism, or bias | Friends may offer advice based on their own views or experiences |

Therapists are trained to notice patterns, challenge unhelpful thinking, and guide you through deep emotional work—skills that even the most well-intentioned friend doesn’t usually have.

As one client once said:

“My therapist doesn’t just listen—she helps me make sense of what I’m saying, in ways my friends can’t.”

Final Thoughts

Therapy works because it combines science, structure, and human connection. It offers both a mirror and a map—helping clients understand themselves while moving toward healthier, more meaningful lives.

Whether you’re navigating anxiety, burnout, relationship issues, or a spiritual crisis, therapy can offer tools and insight rooted in both evidence and compassion. When integrated with Islamic principles, it becomes even more powerful and aligned with one’s deeper purpose.

References

- American Psychological Association (2017). Understanding psychotherapy and how it works.

- Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., Weitz, E., Andersson, G., Hollon, S. D., van Straten, A. (2016). The effects of psychotherapies for major depression in adults on remission, recovery and improvement: a meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 202, 511–517.

- Wampold, B. E. (2015). How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 270–277.

- Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Guilford Press.